Bringing Bond to the Royal Albert Hall

In September 2017, London audiences were treated to a screening of arguably the best Bond film of the modern era, CASINO ROYALE, accompanied by live orchestra. This is the story of the eight-week effort to make this extraordinary event possible.

Nothing quite beats the experience of watching a beloved film in the company of thousands of fellow fans. Nothing, that is, except when there's an entire symphony orchestra there, too, playing the film's soundtrack live, from start to finish.

It's no surprise, then, that these "film-with-orchestra" programmes have become immensely popular over the last few years. If you're a film music fan, such screenings provide a unique opportunity to hear your favourite scores performed in full right there in front of you. And if you're a more casual moviegoer, you can simply enjoy the visceral thrill of seeing a brilliant movie on a big screen, bolstered by that special crackle of energy you always get when living, breathing artists are in the room.

It's a treat to work on these screenings too - and it was an especial privilege to have been involved in this one, the first time a Bond film had ever been given the live orchestral treatment. I'd already had the pleasure of working with composer David Arnold in 2016 when I prepared the score for Independence Day Live, another Royal Albert Hall extravaganza featuring David's brilliant music. The idea of doing Casino Royale was already kicking around towards the end of that project, and so I was delighted when the call eventually came in early 2017.

Now, you might be forgiven for thinking these shows ought to be fairly straightforward to organise - after all, the film's already been made, and the music's already been recorded, right? But in fact they are fraught with behind-the-scenes challenges. These mostly stem from a simple fact about film music: it isn't written with repeat performances in mind. Instead, it is usually destined to be performed once, in a studio equipped with dozens of microphones, and then. . . well, and then that's that. If you're lucky, the score and orchestral parts will be archived somewhere, but rarely with any expectation of their being dug out again for another run-through.

This means even something as simple as tracking down the original sheet music can be quite a challenge. But even if you do manage to find it, there's another major wrinkle: what you see written in the score isn't always what you hear on the finished soundtrack. Changes to the music are frequently made on the podium during the recording session, and rarely incorporated back into the written score. And even more radical alterations will inevitably be made in the editing suite later on: whole bars of the recorded music will go missing, sections might be repeated, entire cues will be spliced together, and so on.

That's why live screenings like Casino Royale in Concert generally require the score to be meticulously rebuilt from the ground up, to ensure that the seventy or so players on stage are playing a version of the music that actually fits the finished film. It's a pretty big but very specialised job, so I thought I'd detail the process in this post for those who are interested in how these things come together.

GETTING STARTED

Initially, it seemed like Casino Royale in Concert might be a much simpler proposition than Independence Day Live. Whereas the music for Independence Day had been written in the era before computerised scores were the norm - requiring orchestrator Nicholas Dodd's entire 600-page handwritten score to be entered manually into the notation programme Sibelius - Casino Royale had been recorded recently enough that the orchestral parts were still available in electronic form. Jill Streater of Global Music Services kindly supplied us not only with scans of Nick's handwritten full score, but a complete set of Sibelius files containing the parts used for the original recording sessions. This was a great starting point.

I also had the good fortune to be working again with Geoff Foster, the Grammy Award-winning chief engineer at Air Studios, whom I had previously collaborated with on Independence Day Live. Geoff had actually recorded and mixed Casino Royale's soundtrack the first time around, which meant we had access to all the original audio from the recording sessions - something which would prove invaluable as the project went on.

Nevertheless, despite these head starts, there were still numerous challenges ahead. These can perhaps be illustrated best by walking through the process of preparing a couple of cues from the film: the first cue, "License 2 Kills", and the theme song "You Know My Name". Helpfully, someone has uploaded a clip from the Royal Albert Hall performance of this sequence on YouTube, so you can follow along:

LICENSE 2 KILLS

THE SCENE: The film's grainy black-and-white prologue immediately establishes a new, grittier tone for the Bond franchise after many years of cartoonish camp. It also serves as our introduction to a newly-minted Bond - not just a fresh face in the shape of Daniel Craig, but a Bond who is himself fresh out of spy school.

The whole film is in fact something of an "origins story": the tale of how Bond becomes Bond. The prologue details Bond's cool-as-a-cucumber assassination of double agent Dryden (Malcolm Sinclair), intercut with flashbacks to a far messier bathroom brawl with Dryden's terrorist contact (Darwin Shaw). During this sequence, Dryden calmly reflects that Bond can't possibly be a "double-O" - that is, an agent who is "licensed to kill" - because it takes "two kills" to acquire such a status. (Don’t ask how this little bit of circular logic works.) Of course, by the end of the prologue, Bond has earned himself a promotion and become the deadly, dashing 007 we all know and love.

THE MUSIC: The first thing to notice about the music is that it begins without orchestra. Instead we hear sinister, synthesised atmospherics. David explained to me that his thinking around this was that audiences have come to associate the character of Bond with a rich, sophisticated orchestral sound - but in this scene, Bond isn't yet Bond. The electronics therefore serve to disorient the audience, while also establishing a more modern sound for this more modern take on the character. (In fact, so crucial to David's conception was this idea of withholding the orchestra that we eventually decided to scrap a live version of the Columbia Pictures theme tune I'd spent several hours transcribing from the original audio. Always the way!)

Eventually, strings and harp join the synthesised drone in isolated fragments - a glimpse of the Bond to come, perhaps. Suddenly, as we cut to the violent fight scene with Dryden's contact, the orchestra bursts in - the kicks and punches onscreen mirrored by pounding percussion and discordant brass stabs in the score. And then, just as suddenly, we are returned to the calm of Dryden's office.

THE CHALLENGE: It is clear that the filmmakers spent a lot of time getting this scene just right, and this is particularly evident in how the music has been edited. The score here is full of numerous short edits and post-production cuts, all of which needed to be re-incorporated into the live score. For instance, when the orchestra does initially erupt, it is in a highly syncopated 5/4 time signature to reflect the disarray onscreen. However, at some point in the music editing process, the percussion parts - which were recorded separately to the rest of the orchestra - were layered in with the brass and strings a whole beat earlier than they appear in the written score, presumably to enhance this rhythmic tumult still further.

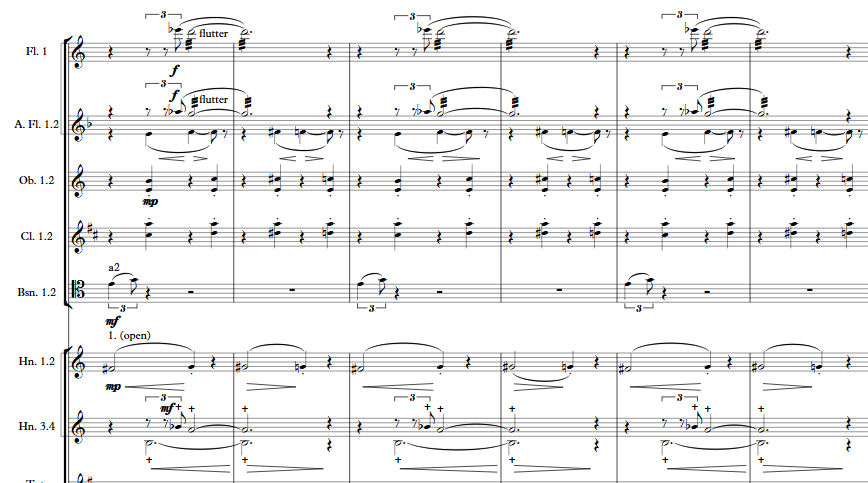

These sorts of post-production edits are typical in tightly edited action scenes, and only through careful listening to the final music stems is it possible to locate and incorporate all the necessary changes. It's also common for instrumental parts to be added or removed during the recording sessions themselves. A scurry of violins accompanying the orchestra's second frenetic outburst, for instance, was nowhere to be found in the original manuscript or parts and needed to be added to the live score (below).

We were also working with a slightly smaller orchestra than was used in the original recording sessions. Notably absent here were two of the six trombones originally called upon to play dissonant clusters in the fight scene, and this meant a bit of reorganisation was necessary (thanks for the help, bassoons). Still more reorganisation was needed for the percussion parts, too, to ensure that the twenty-nine percussion instruments called for in the final score could be tackled by just five players. (I use an Excel spreadsheet for keeping track of who's playing what, in case you're wondering!)

After a high, sustained violin note - once again absent from the original score! - a crescendo leads us into…

YOU KNOW MY NAME

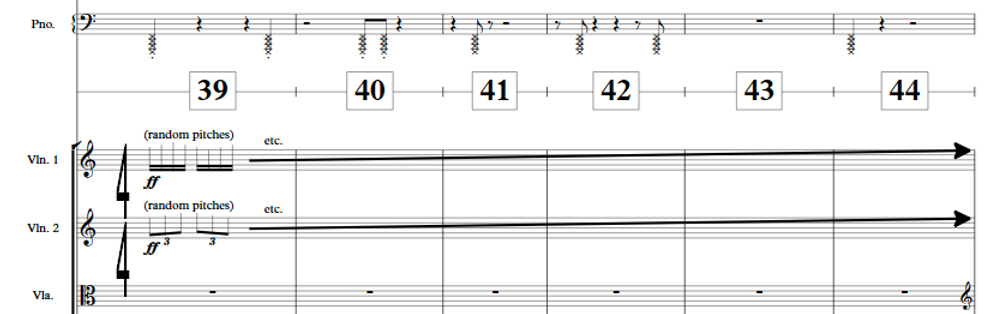

THE SCENE: "You Know My Name" is set to a title sequence by the great Daniel Kleinman, who has designed every Bond title sequence but one since 1995's GoldenEye. It's everything we except from a Bond title - dynamic silhouetted figures, stylised violence, imagery drawn from the film (in this case, a playing card motif) - but with one major difference: there isn't a Bond Girl or villain in sight. This is James Bond stripped bare, standing alone against the world.

THE MUSIC: Chris Cornell and David Arnold's song starts by introducing the very catchy tune (above) that will become Bond's key motif for the remainder of the film. (Monty Norman's iconic "James Bond Theme" doesn't make an appearance until the closing credits in a cue appropriately called "The Name's Bond… James Bond".) The song's chorus is based around a variant of the famous Bond "vamp" attributed to John Barry, a restless series of rising and falling chords that instantly say "secret agent" no matter what the context.

"You Know My Name" also finally introduces the orchestral colours we typically associate with the Bond universe: electric guitar, bass guitar and drumkit, alongside raunchy orchestral brass and a lush string section. Given the importance of this particular sound to the film, we decided to include all three of the non-standard "band" instruments in our line-up, alongside the more usual orchestral suspects.

THE CHALLENGE: There were, however, still a few things in the song that could not be replicated live. Chief amongst these was, of course, Chris Cornell's inimitably raw vocal performance. Tragically, Chris Cornell passed away shortly before we began work on the project, and David quite rightly wanted to pay tribute to his memory - and his enormous contribution to the film - by leaving his vocals intact on the soundtrack.

Also mixed into the song were several multitracked guitar parts, recorded by David in his studio, that we felt would be impractical to recreate live. However, because these parts were highly rhythmic in nature, and because they had to match our live drummer, this meant we would have to co-ordinate the pre-recorded elements very tightly indeed with the live players.

Of course, keeping an orchestra in sync with the movie is bread-and-butter work for a film conductor, and luckily we had a very talented one in the form of Gavin Greenaway (who also did sterling work on Independence Day Live). Usually, a film conductor ensures everyone hits their mark by watching a version of the film on a special video monitor, which at key moments displays a vertical stripe moving from the left-hand side of the screen to the right. When these so-called "streamers" reach the right-hand side of the screen, a large dot flashes up for a single frame (called a "punch" after the hole punch that was originally used to achieve the effect) and this acts as a visual synchronisation point. (You can read more about streamers and punches here.)

However, this has its limitations, and Casino Royale in Concert hit hard up against them. Not only did our orchestral players need to synchronise with the picture, but they also need to play perfectly in time with those pre-recorded elements: just a handful of milliseconds' delay between the live drumkit and the rhythm guitars on the soundtrack would sound catastrophically out of time.

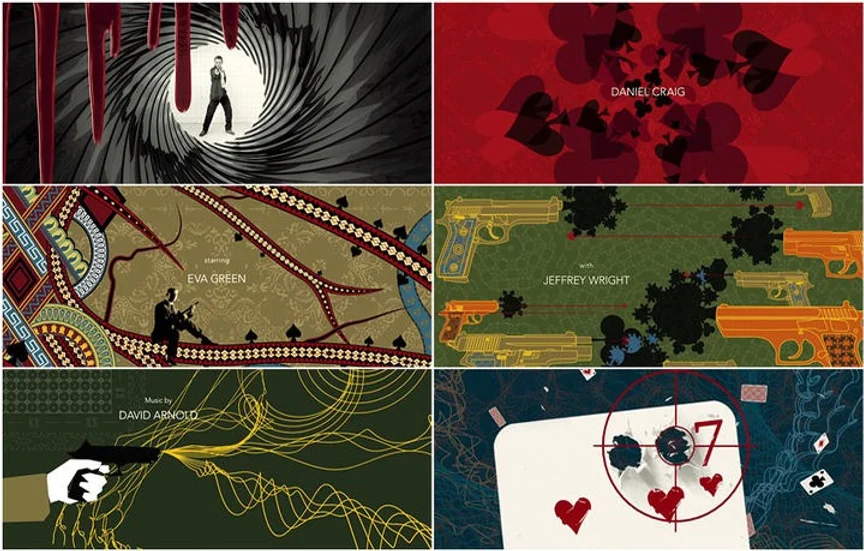

So the decision was made to put the whole orchestra "on click" - that is, provide every player with an earpiece playing back a pre-recorded "click track", a constant metronome sound that tick-tocks away dynamically as the tempo fluctuates up or down. Click tracks have been around since at least the 1930s, and performers have always tended to grumble at using them, because their rigidity can inhibit the music's expressive possibilities. But when an existing musical performance needs to be matched perfectly in terms of tempo, there's little other way forward.

The difficulty with "You Know My Name" was that it wasn't originally recorded with a click track - it's a rock song after all - meaning that retrofitting one would prove a complex and time-consuming process. Thankfully Geoff Foster did much of the heavy lifting, meticulously going through the track bar-by-bar, beat-by-beat, and making little adjustments in Pro Tools so that the clicks there would match the tiny fluctuations of tempo in the original recording. I was then able to use this Pro Tools "tempo map" to synchronise a virtual playback of the orchestral score with the original audio files, meaning we could hear a very good approximation of how the two elements - live orchestra and pre-recorded audio - would sound together.

It took a lot of back and forth to make this work, because if any one of those minute tempo changes was incorrect, it could have a knock-on effect for the rest of the track. The process took a full day or two of work - for a song that lasts just two-and-a-half minutes! But in the end it was worth it: audiences hearing the finished product would find it impossible to tell where the live music begins and the pre-recorded music ends.

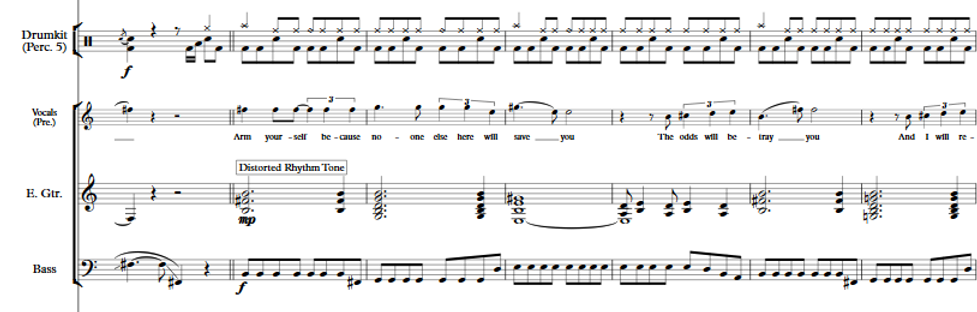

Of course, the other challenge with a rock song is that the band parts are almost never written down. Such was the case here: while we had parts for the orchestral brass and strings, the lead guitar, bass guitar and drum parts all needed to be transcribed from the audio so that they could be accurately reproduced on stage:

This is where it was once again hugely advantageous to have had the original recording session files - I was able to isolate each instrument in turn, which made the job of transcribing what I heard infinitely easier.

END CREDITS

Of course, these were just the first two cues out of a total of 43 - the final orchestral score numbered over 400 pages and took eight weeks to prepare, not including the parts (which were prepared by JoAnn Kane Music Service, along with a section of the Act II score). But the challenges faced in these cues are emblematic of the whole project.

Preparing a score for one of these concerts requires a bit of everything: music editing, engraving, audio transcription, arranging, building click tracks, preparing mockups - and even making a few wholesale alterations to the original score to accommodate things like a newly-inserted intermission, or an extension to the end credits sequence.

On that last point, perhaps my favourite part of this job was having the opportunity to add a little sauce to the "James Bond Theme". The end credits for Casino Royale traditionally feature a version of this theme (in David Arnold's and Nicholas Dodd's excellent arrangement) followed by a reprise of "You Know My Name". But we wanted the whole orchestra to play through to the end of the credits, which necessitated a longer version of the "James Bond Theme".

What we ended up doing was repeating select passages from the cue several times, but reorchestrating them in order to provide a bit of variety. This is how I got a chance to rewrite the "James Bond Theme" - even if only for a few bars! So if you ever attend Casino Royale in Concert - and I'd strongly urge you to do so - keep an ear out for that passage during the credits featuring tremolo strings and flutter-tongue flute: my own little contribution to the world of Bond music.